UNITED STATES—The filmmaker Everett Lewis with whom I was collaborating on “The Strawberry Butterfly” used to peer down and say “yep yep yep” when a scene in the screenplay clicked. The pages mounted, almost effortlessly; the Brother Word processor kept humming. Finally, come December, Everett took one last look at the batch of pages, now over 105, and said a conclusive, “Yep yep yep.”

We had our final meeting at the Vagabond.

I got a set of copies made at an ugly mini-mall where there’s apartments now on Vine and Sunset. Back at the house I remember Dee being so excited, she thought the stack of copies in mauve covers looked so official. Then the following Saturday, I was to deliver them to Everett at the House of Pies. This was one of those times when I was painfully puntual. As the appointed hour came, I was in a revival house, watching for the very first time Alfred Hitchcock’s “Strangers on a Train,” and I pulled myself away from the final reel, which is one of cinema’s most bravura pieces of uninterrupted poetry and suspense.

To escape the movie’s gravitational pull at this point in the drama was quite a feat. And there we were, in the House of Pies, where I’d had my first conferences about “The Strawberry Butterfly.” Everett and I now shared the glow, the satisfaction of shared creative accomplishment. And I was gratefull to Everett, he had allowed me to get the kinks out of my original screenplay.

He picked it up and said, a sly look in his eyes, “I smell money.”

I liked the sound of this. And with the turning of the last page on “The Strawberry Butterfly,” my heart was ready to turn another page. At this time Mexico came back to me and the world in a big way: the North American Free Trade Agreement had been ratified in Congress. Lupita Jones was Miss Universe, and a year earlier the poet, Octavio Paz was awarded the Novel Prize in Literature. It was as if the Los Angeles effect was happening in Mexico.

Something was happening there, a creative and economic fervor. I strongly got the feeling, as when I lived in Memphis and would call Los Angeles, my friends were doing things, things were happening in Los Angeles and I was missing out. Likewise Mexico.

We had the screenplay now. I could turn elsewhere and travel a new road. In this buoyant frame of mind I took a break from Los Angeles for a Christmas visit with my family. My reconnecting with them was by now whole and complete. It makes me think there can be no bad love in the world; it can be foolish, lost and half-blind, but it returns and when it does, it still deepens and unifies everything.

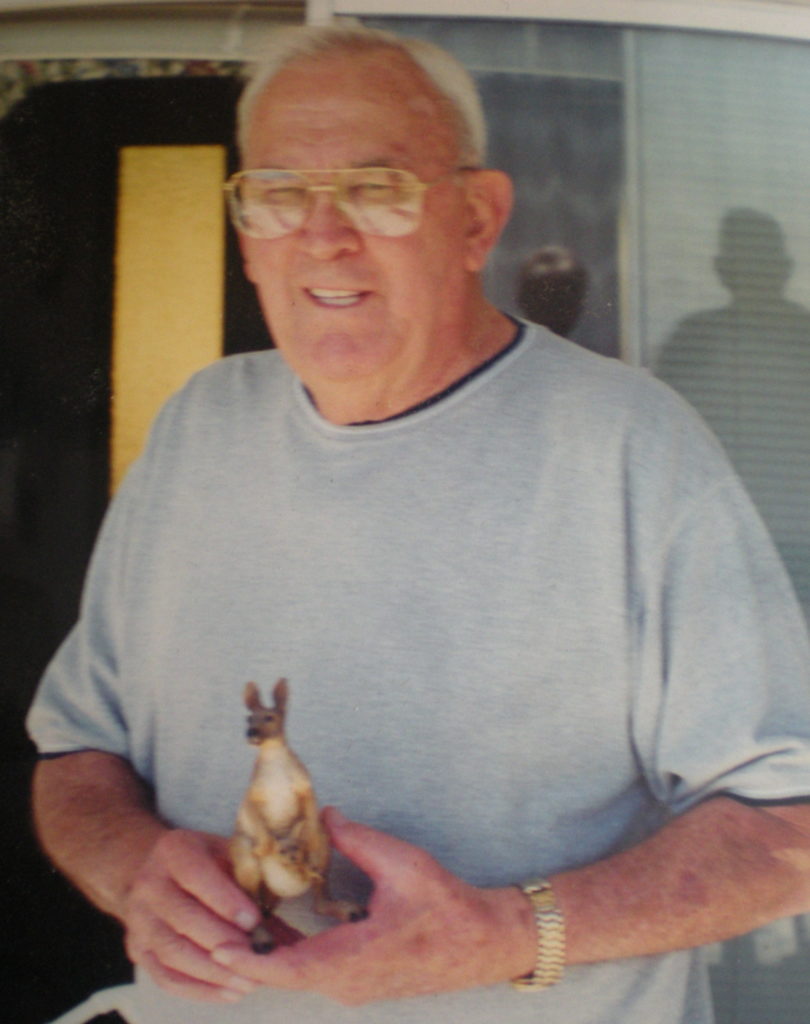

That Christmas in Watsonville my aunt and uncle had come up from Taft. Their son, my cousin, has died from AIDS only a year before, I’m sure this still weighed on them. It’s not something we talked about and I didn’t initiate that talk. It had been a few years since I’d seem them: my aunt was the same as ever, my uncle seemed heavier, his hair suddenly more white than black. We went with my dad to Danny’s, the little diner in the rambling wooden local shopping center. Uncle John was my favorite uncle, he was my only uncle, but trust me, if you knew John, he’d be your favorite uncle too.

I was beaming about the screenplay at the breakfast table, of eggs, pancakes, hash browns and coffee constantly poured by the girl with the tattoo arms.

“How soon do you think you’re going to sell it?” John looked at me, dark eyes through wire gold glasses.

“In two months,” I said flatly